Part 1: Land Art + Building in the Landscape

The following essay would discuss ideas and theories of East and West and how they influenced modern landscape design.

Chapter 1. Introduction

Since ancient times, our ancestors had shown their respect to nature by using land art to express such admirations. In China, places are protected where the feeling of spiritual connection is the strongest. In England, classical gardens are admired for its form and space. During the course of history, the East and the West developed and formed different aspects of art and philosophy. These cultural differences come to a clash during the 20th century and both societies had interacted and influenced each other greatly. This resulted in a world society we live in now.

Looking through the eyes of ancient oriental culture, many of the land art, which the people of today consider to be, were in fact not meant to be. A stone, a statue, or a tree in one’s garden is mainly for decoration and aesthetical uses and not to be considered as land art. It represents only one of the elements of harmony. Since harmony is considered to be the essence of all kinds of art (including social art and spiritual art), the harmony of the whole is more important than individual elements. To truly understand this idea, one would need to look at the whole picture to experience the great view.

Figure 1. Giant cloud-rocks in Nan Lian Garden. They do not serve as main characters in the garden but a humble part of the whole journey experience.

In fact, in Chinese landscape planning, Chinese ancestors categorized the natural elements into 5 categories: Metal, Wood, Water, Fire, Earth. These elements have different characters and must coexist to gain a harmonious balance. The way to interpret this relationship is called “Feng Shui”, literally translated as “wind and water”, which means the elements in nature, will greatly influence the beneficial aspects of people and other creatures living there. It is a Taoist point of philosophy that all forces of the universe (either human or nature) have to be in balance in order to survive.

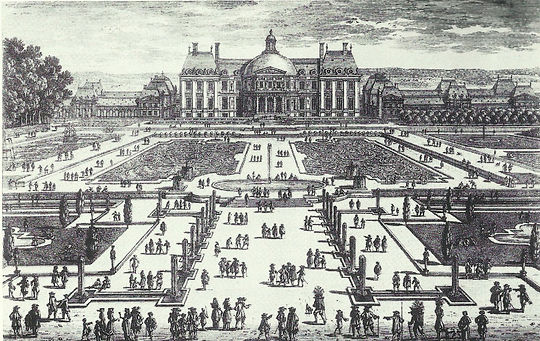

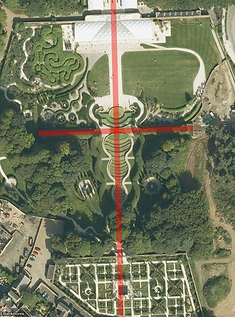

The western concept of land art is very different from their counterpart. For they do not have the concept of “Feng Shui” to incorporate with nature, but like a composer, armed with the idea of the biblical role that man being the lord of all creations and center of the universe, creating a picturesque garden in his own way. This design approach can be very creative as there are no rules to guide or restrict their limitation, but would bring negativity if one fails to handle it properly. Since ancient Roman times, most garden design does not fit with the natural course of landscape but have a strong notion of man above nature or the center of the universe. Most architectural design could identify the straight cross symbol on their plans (Kassler, 1964, p.7). Such design concepts influence modern western landscape design and such concepts are visible in Gardens of Vaux-le-Vicomte, the White House Gardens and Alnwick Garden. In western culture, and even in modern America, people would view landscape design as a job for architects instead of a job for artists. Most of those designs are centered on functional uses and the comfort of man and most are in symmetrical patterns. Their way of harmony can be described as subjective because until the seventeenth century, Europeans designed their gardens as paintings and compose it on canvas. This would limit the garden’s space in harmony with the place as the design is based on the aesthetic of a perspective painting.

This does not mean westerners could not establish their relationship with nature. They establish such relationship in their own way. They started a new language as a subjective expression of their feelings and a way to interact with their environment. Such as the cross symbol, the item itself might not be in harmony with the environment but it shows the artist’s relationship with nature. This is because they lack the design concept of “the spirit of the place”.

Figure 2. Gardens of Vaux-le-Vicomte, designed 1656-61 by Andre Le Notre, from a seventh-century engraving by Perelle. Nature played a subordinate, almost extraneous part (Kassler, 1964, pp. 4).

Figure 3. View from the private chateau, Vaux-Le-Vicomte. Modern day photo of the Gardens of Vaux-le-Vicomte. From this angle the garden present its grandeur to its visitor and one can simply capture everything from a single view (Petro Photo, date unknown).

Figure 4. Aerial view of Gardens of Vaux-le-Vicomte. This photo shows the cross in the middle and a strong symmetrical design. Same biblical concept of man above nature and man is the center of the universe (Scazenave on Flickr, date unknown).

Figure 5: The White House Garden aerial view. A red cross superimposed on the image shows the symmetrical pattern and biblical cross with the White House at the intersection (Google maps, 2013).

Figure 6. Arial view of Alnwick Garden. The same cross pattern can be seen from the plan of Alnwick Garden (Google maps, 2013).

Chapter 2. Genius Loci

The concept of “the spirit of the place”, or genius loci, does not appear until Alexander Pope’s original interpretation in 1731 (Kassler, 1964):

Consult the Genius of the Place in all;

That tells the Waters or to rise, or fall;

Or helps th’amnitious Hill the heavens to scale,

Or scoops in circling theatres the Vale;

Calls in the Country, catches op’ening glades,

Joins willing woods, and varies shades from shades;

Now breaks, or now directs, th’intending Lines;

Paints as you plant, and, as you work, designs.

His interpretation of genius loci is similar to the concept of ancient oriental artists planning out their gardens: The first line of the poem shows his intention to “consult” the land, to pay homage to the place and knowing what would be best for the land and be able to benefit both human and the environment. The second line is to understand the direction of flow of water, where the ponds should be, and positions of waterfalls. The third line is concerned about the position of mountains, and according to their flow to create paths that would circle around them. Fourthly comes the sense of space, the sound of the place, be it lush or still, the pattern of light from the trees shades. Last but not least, it is important to know the art of work. Instead of focusing so much on the speed of completion, we should allow the process to follow their natural course. For example, if a gardener discovered a habitat during his excavation, he would have to stop and reconsider his plan in order to preserve the animals, so that his garden can blend in with nature.

Modern architectural education emphasize greatly on the importance of genius loci. However, the interpretation of it is centered on the sense of space rather than on the natural environment since most people dwell in urban cities and have less contact with nature now. This resulted in a huge change in concept in modern urban human-nature relationships. It can be seen in the following few examples. Modernist created their own language with nature based on their current knowledge, methods and believes. In other words, their interpretation of place is mixed with their own feeling of place and personal characteristics, creating a new alien language. A group of self claimed conceptualists (a specific group of avant-garde modernists) have isolated art from nature since city dwellers had long lost the connection with nature. They created a new “reality” of nature (eg. plastic tree trunks) for the city dwellers and claimed it would look more harmonious than planting a fake garden. This idea will be further discuss in Chapter 5.

Chapter 3. The Concept of Oriental Garden

The origins of oriental gardening design come from China. During the Tang Dynasty (Running from AD 618 to AD 907), Chinese culture has strongly influenced eastern Asia especially Japan and Korea. Buddhism, Daoism and Confucianism were Tang’s national and cultural believes. These theoretical thinking were applied to daily lives to the extent of construction of temples and landscaping design. The essence of oriental garden is based on harmony between human and nature, such relationship can be described as “human and nature as one”. Such respect and emphasis on human relationship with their environment (and could further developed as the truth of universe) could be stronger than any aesthetic or functional reasoning implication during a design process.

In ancient times, artists built most gardens as they view it as a piece of art instead of architecture. Most gardens were built as a place for meditation. It is the spiritual essence of harmony (or a feeling of at peace) in human and nature relationship that the ancients priced most.

Here is a poem by Tao Yuanming, also known as Tao Qian, a Chinese poet in Jin Dynasty describing his feelings to his garden.

飲酒詩二十首之五

I built my house among men

But no sound of horse of carriage disturbs me.

How can that be?

In the remote heart, every place is a retreat.

I picked the Chrysanthemum at the east fence,

Watching the southern mountains

The atmosphere was high

Birds are returning to their nest.

There are deeper meanings in such things,

But I have forgotten the words to express them.

Poems of Tao Yuanming (365-427)

In this poem Tao described the atmosphere of his garden and the essence of the Chinese gardening design. In Chinese landscape design theory, the ancestors designed their gardens as a miniature version of the universe. Human and nature coexist in an environment in a harmonious way. Both benefit from each other and blend together harmoniously. Everything fits in their assigned place as if they were born to be there. Therefore everything has its own spirit, always changing, self-maintaining and alive. The “quality without a name” (Alexander, 1979) could be found there. The poet felt it, and would be the same living garden we can feel today if the harmony was not broken. Such deep and complex feelings could not be expressed through words; thus he reserved his speech to allow us to experience it for ourselves.

During Ming Dynasty, in the year 1631, “Yuan Ye”, otherwise known as The Craft of Gardens, written by Ji Cheng, was the first Chinese document on the design of landscape gardening. In this book he described many practical uses of architectural design principles and technique in Chinese gardening design.

In it, he mentioned the art of borrowing; which is to use existing external environment or interacting existing objects in the garden to form a picturesque scenery. This technique adds depth to the scene and enriches the view.

Another theory that influenced oriental landscape design is “Feng Shui”. It can be considered as mythical believe but in truth, practical science. Similar to the art of borrowing, it borrows the existing “forces” of the site to achieve a proper balance. This is done in harmony with nature through locating, orientating and designing structures, gardens, etc.

Figure 7. The “Feng Shui” compass (also known as Luopan) still being used today. The annotated list explains the 18 layers on the compass in Chinese

(http://www.iching.com.my/loupan-en.htm, 2012).

Chapter 4. Cultural Clash

Most westerners rarely knew much about Chinese culture until the 20th Century. It was when China first joined the world fair in The Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904 (better known as the St. Louis World’s Fair) that the West started to take notice.

According to Huang (2005) and the bureau of Shanghai World Expo Coordination (no date), although the Pavilion and many cultural items were awarded, China did not participate after 1904 due to the limitation of national power. In 1982, Chinese representatives contacted the Bureau International des Expositions (BIE) leaders. Following in 2010, China received the opportunity to host the world expo in Shanghai. During the period between 1904 and 1982, China had closed her doors to outsiders. Therefore, for westerners, the easiest and simplest way to learn about oriental art and theory would be through Japanese culture.

Wright gained interest in Japanese culture in 1893, when he visited the world fair in Chicago. The simplicity of Japanese culture, blended with the theory of Buddhism, fits in with Wright’s organic thinking perfectly. He wrote: “At last I had found one country on earth where simplicity, as nature, is supreme.” (A.Y. , 2012) After several visits to Japan, Wright designed the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo (1923).

The construction of Imperial Hotel is an attempt at combining Mayan and Japanese traditional architecture. By the Art Deco jazz age of the 20s-30s (Larson, 2012), it was considered exotic as well as something the visitors from all over the world could relate to. This bold attempt results in a very rough westernized oriental hotel, which looks alien.

In the following images we can see the similarities of the proportion between a traditional Japanese temple with the Imperial hotel front facade.

Figure 8. Imperial Hotel front façade. (Larson, 2012)

Figure 9. Byodo: A Buddhist temple in Phoenix Hall, Uji (1059), Kyoto, Japan. (Larson, 2012)

The Japanese influence in his later works is essential, including the famous Fallingwater in Pennsylvania. Fallingwater has a strong Taoist philosophical in which “human and nature as one”; simply put, blending naturally with nature, what is now known as the Organic Style. His prominent influence in modernism started a trend of Japanese and oriental culture followers.

Figure 10. Fallingwater was completed in 1939. From its exterior, the Japanese architectural proportion of spreading out horizontally can be seen in its design pattern (Fallingwater.org, 2013).

According to Kassler, if we take a look at western garden design history, landscape art has always been considered as a form of architecture instead of art.

“We are out of joint with nature, and out of joint with our own natures as a consequence.” (Kassler, 1964, p.6)

The above statement can be interpreted as: Westerners had long lost their joint with nature since the Industrial Revolution, and lost their senses with their own nature as a human being. Blocks of building were built for practical uses and lack humanity. They are accustomed to living in small apartments with little to no exposure to the natural elements except the concrete streets and cement blocks. Although humans are very adaptable, long isolation from nature has caused them to be disjointed with nature. It would be difficult for city dwellers to reconnect with their human nature. Therefore architects seek new ways to reestablish the relationship from a design point of view.

In 1923, Le Corbusier’s “Towards an Architecture” states five principles of modern architecture. They are:

• Freestanding support pillars: to lift the building from earth, in other words, to touch the ground lightly. This is to leave as little impact on the environment as possible, to protect the natural state (be it a historical site or a wild life area) and create a sense of living on trees.

• Open floor plan independent from the supports: can be implied as living in a forest. Since being in the woods nothing is fully enclosed. It is another nature of human beings who do not like to be enclosed in inflexible small cell rooms.

• Vertical facade that is free from the supports: to create a visual impact like as if we are living in the clouds.

• Long horizontal sliding windows: to have a view of the surrounding neighborhood. There are two forces that act in us as a human being. At one hand we would like to be protected from the elements, but on the other hand it is human nature to be curious, aware of and be able to contact our environment through visual and physical impact.

• Roof gardens: to replace what was there originally if we had taken something out from nature.

As people pay more attention to the importance of the human-nature relationship, they will learn to go back to their natural-selves. The five principles are primarily based on our primitive senses on how we live when we were cavemen. We are returning to our true nature as we respect our natural environment.

Chapter 5. Case Studies

Professor Yu is one of the most influential Chinese architects. Yu’s doctorate from Harvard and Chinese philosophical upbringing have helped shape his perspective on landscape design. His work is the perfect combination of east and west, science and art: a modernist expression of ancient wisdom, human and nature as one using scientific methods and geological knowledge applied to his designs with modern techniques.

According to CCTV13 news (Saunders, 2012), Yu was described as using very simple scientific ways to resolve the imbalanced harmony between man and nature. This description was compared to ‘… American designers and European designers who are more concerned about form and art.’ These designers are named Avant-garde designers. Examples of Avant-grade designers and their philosophy can be found in Avant Gardeners (Richardson, 2008). One of the philosophies mentioned is “Maxims Towards a Conceptualist Attitude to Landscape Design”. In it, the problems with plastic is worth mentioning and is as follows:

1. We already live in a plastic landscape, and can even imbue it with meaning and emotions.

2. A hatred of plastic is a hatred of humanity.

3. Plastic toys can be more fun than wooden toys. Plastic trees can be more fun than wooden trees.

4. What is artificial is true to itself.

This argument proposes that since we are already living in a plastic world, we should accept it as part of our true selves. Therefore, a plastic forest would be more true to itself than a mock up forest.

One of the examples supporting this argument would be the Lipstick Forest in Montreal designed by Cormier in 2002. The plastic tree trunks colour relates to the history of the site, as it was a cosmetic industrial city.

“It is all about this notion of something that is artificial but not false. We were asked to create a winter garden inside a convention center…yes we could have used real plants, but it would have been so false.” --- Cormier (Richardson, 2008, p. 74)

Figure 11. Lip Stick forest interior perspective (Vézina, 2003).

Figure 12. View from corridor can see plastic trees arrangement (Vézina et al, 2003).

Figure 13. (a) Night scene (Vézina, 2003) (b) The corridor on the right seems more welcoming than the one on the left (Galland, 2005).

Just like cosmetics, such aesthetics would only be a spark of excitement. It is good for company branding but has nothing to do with the user’s true self. People won’t feel comfortable dwelling in a bright-pink forest for too long. It is the kind of colour that fast food restaurants use to push their consumers to eat quicker so they can have the space for the next visitor. This statement could only be true to this plastic society but not to all humanity.

According to Yu’s “Big Foot Revolution” statement (Yu, 2011), we should not follow blindly and let what this generations’ mainstream cultural aesthetics influence and twist our judgment on values of health, prosperity and true beauty.

One successful case can be seen from his Red Ribbon Park design in Qinhuangdao City, China (2008). The site is alongside a river. He challenged the Chinese local authority in how they would usually approach urban planning. The conventional way was to let engineers build concrete slabs on the sides of the river to reinforce the pavement, then allow gardeners plant flowerpots to decorate the sides. Yu claimed such an operation is “small feet” beauty, just like an ancient Chinese lady who binds her feet, indirectly damaging her own health, in order to fit into high-class society. It ruined the natural beauty (the so-called “messy” grass) that was already there. On top of that high maintenance is needed for the flowerpots that are not meant to be there.

Like how the Chinese ancestors would plan their ancient garden, instead of imposing what the designer intends to place on the land, we should be friends with nature and make good use with what was already there. Yu believed that the best formula to resolve most landscape design is:

Wild nature + minimal intervention + low maintenance

He persuaded the authorities to preserve the wildness of the place as part of the scenery, and use local plants to form a natural spongy shore to overcome the rainy days and flooding seasons. The plants, being local, fit in the environment perfectly and no maintenance or mowing is required in all seasons. The only additional element he placed there is the 500m long red bench. It blends in with nature perfectly as it has potholes allowing grass to grow through. It also functions as a light box during nighttime and bring romance into the scene. The red ribbon bench contrasts with the green around it and opens to the river scene, bringing the neighbourhood together and has now become a famous tourist sight. This minimalist design brings the once malfunction area alive again. It gives the users a place to reminiscent the old rural days, and nurture relationship.

Before Construction

Figure 14. The site of Tanghe River before construction of Red Ribbon Park. It was full of waste and pollution. (Turenscape, 2008)

Construction Plan

Figure 15. Detail of the long bench (Turenscape, 2008).

Figure 16. Planning of the Red Ribbon Park (Turenscape, 2008).

Figure 17. Red Ribbon Park satellite photo from Google Earth (Turenscape, 2008).

After Construction

Figure 18. Summer day scene showing grass growing through potholes. The red colour contrast brings out the green around it (Turenscape, 2008).

Figure 19. Summer night scene. The red ribbon bench acts as a lighting box at night. (Turenscape, 2008).

Figure 20. Winter day scene (Turenscape, 2008).

Chapter 6. Conclusion

Man can lead a better life if he can be harmonious with nature. In architecture, one can see the wisdom of man in this aspect. Different architectural styles were employed in western and eastern architectural constructions to express their different concepts and ways of harmony; these concepts influence our contemporary architectural design in various societies. The next part would compare Alnwick Garden & Nan Lian Garden to discuss ideas and theories of East and West, and how they influenced the landscape and garden design of today.

Part 2: Comparison of East & West

The following essay would use modern examples in East and West to compare their ideas and theory.

Alnwick Garden, Northumberland, UK

A classical garden becomes a new tourist attraction.

Chapter 1. Garden History and Design Philosophy

Wirtz (1999), “Alnwick Garden is a private garden where 5 hectares are accessible to the public. It lies in the borders of the City of Alnwick in Northumberland, 10 minutes from the North Sea coast and Edinburgh.”

The garden has a long history of development. It had been laid down by Hugh Percy, the 1st Duke of Northumberland, in 1750 and became prosperous during the mid 19th century; when Algernon Percy (the 4th Duke) brought seeds from all over the world and created an Italian garden with large conservatory. During the Second World War it had been used as a Victory Garden to provide food for the country. It was then closed down as a working garden in the 1950s. After a period of stagnation, the Duchess of Northumberland decided to revamp Alnwick Garden with the hope of making it into a mecca, situated in North-East England, for garden-lovers (The Economist, Garden Design: Power Plants, 2001).

The Economist claimed that Wirtz style is distinguishable “by a clearly- contoured, geometrical quality that is as effective in winter as it is in summer.” In an interview, Peter Wirtz said: “The plant material always plays the first violin. We search for the tranquil spirit, never for conflict.”

Their trump card is “Respect for the existing situation, climate zones and plant habitats, the excellent design, the constant focus on well balanced sustainability, attention for details and supervision from the beginning to the completion of every project.” Their design philosophy is “ focus on reality during the design process” and “a deep-rooted passion for plant materials”. Their formula to design is to link a terrain “to a series of existing details: a city transport system, a historical monument, a private home, the headquarters of a company, a museum and a part of its collection (Wirtz, 1999).”

Figure 21. The fountain became a spine for the garden, it forms a biblical straight cross in the middle of the garden. (Wirtz NV, 1999)

Wirtz’s attention to detail creates a series of unique elements linked in each garden. For this garden, the following can be seen:

“The spine of the garden was formed by a curving cascade and hornbeam bowers, leading to a geometrically decorative garden with borders of blooming plants and roses (Wirtz, 1999).”

Figure 22. A3 pamphlet maps handed out to visitors, commissioned work by Sarah Farooqi (2012).

Alnwick garden houses a rose garden, a bamboo maze, a Medicinal Herb Garden (The Poison Garden) and a water garden (The Grand Cascade) (Wirtz, 1999). All those elements do not work together as a coherent whole and each have their own theme of characters. All elements are connected through an ordered cross floor plan (see map in p. 8). Such elements were placed into the landscape according to the designer’s concept of touch of nature (or respect to nature), and yet they are not arranged in harmony with nature.

Chapter 2. “Respect to Nature” and “Harmony with Nature”

Going through the pavilion area, we can see the strong Italian style main entrance with the eye catching straight axis Grand Cascade(Figure 24). The use of water, which is Wirtz’s design pattern, as it flows through different parts of the garden and guide the visitors through the walks.

Figure 23. Main entrance of the garden.

Figure 24. The central Grand Cascade.

Figure 25. The cross section of the garden. The highlighted area illustrates how the whole view of the garden could be seen at the top of the hill.

From the main entrance point of view (Figure 23. on p.28) the visitor can almost take in the whole garden with one glance. It lacks depth or mystery as the plan is very clear and symmetrical. Setting against a slope, it gives a dramatic grand feeling of a great entrance, other than that, there’s nothing much to excite the visitor as one can see everything from the vantage point at the top of the hill (Figure 21. on p.26).

The garden does not integrate much with nature but built itself as individual elements linked together. The visitor could not transit between elements smoothly along the main circulation path but have to locate and seek them out through out the garden in order to approach them. Most visitors would approach the Oriental Garden through the Grand Cascade, then walk all the way back down from the other side and pass the bamboo maze. The Rose Garden, Cherry Orchard and the pond could not be located without the help of the map, because they are located behind another element off the main road that visitors might miss. This is due to the whole site being planned out as picturesque scenery like a beautiful backdrop in the theater. The flower booth would be in full bloom during summer but barren in winter thus reducing the number mystical places to involve one’s imagination. In addition the bamboo maze was not planned and maintained adequately.

Huge trees are sparsely separated in the fore and middle ground of the garden with climbing plants on wired fence occupying the rest of the space; resulting in the lack of shading from the winter sun. The form and shape of the plants are tightly controlled and the garden loses its colour when the leaves are lost. If the idea of symmetry in plan is to be applied, an open grass field in front of the visitors’ pavilion contrasting it with the dense bamboo maze would be too great a difference. All elements in the garden do not blend together smoothly, and with its site environment as well (grass hills or taller trees around the area).

Figure 26. Wired frame with climbing plants and barren trees surround the Grand Cascade. The garden lacks shading during the day.

Although Wirtz had claimed that their respect to nature, i.e. their attention to detail and use of plants to compose a beautiful garden in its own rights had gained them success; but if a garden cannot co-exist with the natural forces and be self-sustainable it is not in harmony with nature and therefore, it cannot be considered as having a “tranquil spirit” as Wirtz proposed.

Figure 27. Bamboo Maze. The overgrown bamboos are too packed and bugs thrive there due to lack of sunlight. An all-season garden is absent though it was claimed by the Economist and proposed by Wirtz. The garden itself is quite unsustainable without high maintenance.

Figure 28. One of the existing elements connected to the garden, the tree house restaurant.

Figure 29. Oriental Garden.

Figure 30. The Poison Garden is another theme attraction in Alnwick Garden.

Figure 31. Poison Ivy Tunnel to the Poison Garden.

Nan Lian Garden, Kowloon, HK

A modern garden based on Tang Dynasty garden design.

Chapter 1. Garden History and Site Environment

Nan Lian Garden is a modern public garden proposed by Chi Lin Nunnery and sponsored by the Hong Kong Government (opened to public in 2006). It is located in Diamond Hill, a green island in the middle of an area surrounded by residential buildings, traffic high way, shopping complexes and metro connection. The garden is connected to the Nunnery through a high bridge.

Figure 32. The site is surrounded by highways and residential buildings (HK Govt, 2006).

Figure 33. A blue print of the Tang Dynasty garden Jiangshouju, the garden belonged to the governor of Jiang County (HK Govt, 2006). The Chinese indication shows different function of each area.

According to Nan Lian Garden official website (2006), the design concept of the garden came from the blue print of Jiangshouju, a Tang Dynasty Garden. Though different elements were allocated to different areas, the main theme of the garden is to be in harmony with each other and with nature.

Located in the middle of a triangle traffic high way, the engineers used 260 pieces of soundproof panels to surround the entire garden. This green island is built in a crowded area; which is a surprise to many tourists. This heavenly garden fully transients the poet Tao’s idea of “retreat in the remote heart”. The garden gains popularity due to its convenient location and tranquil atmosphere.

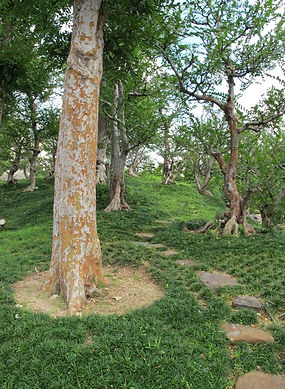

Figure 34. Satellite photograph of site before construction. Nan Lian Garden is located south of Chi Lian Nunnery connected with a stone bridge (HK Govt, 2001).

The garden aims to function as a place for quiet contemplation, meditation and repose. When the tourist is walking on the pathway, every turn would bring in a new angle and a new perspective. The secret of an intricate garden is to have undulating fields and twisting paths for different views. The road and the scenery would function as one instead of having different elements linked to each other by pathways similar to the plan of Alnwick Garden . Trees and corners prevent one from taking in the whole garden in one single view. There is always more to discover on every trip. The main elements in the garden are: plantation hills, vegetarian restaurants, tea house, natural stone craft museum, timber architecture museum, souvenir shop, arts and cultural exhibition hall, golden temple, fish ponds and pavilions. Splits from the main road guide the visitor smoothly from one element to another.

Chapter 2. Feng Shui and Design Philosophy

The whole garden truly represents the idea of harmony based on the concept of “Feng Shui”. The four main themes in this garden (wood, water, stone and buildings) can be categorized into the five natural elements (Metal, Wood, Water, Fire, Earth). They spread evenly in every corner and can be found at the “correct” position. According to “Feng Shui”, the traffic highway surrounding the area can be viewed as Water since it is always flowing. The tall residential buildings would be seen as mountains and thus represent Earth. In that case, trees, representing Wood, are needed to counter balance the two existing elements. Rocks and structures in the garden would be considered as Metal. Lastly, the kitchens and the sunny weather represent Fire. After considering the heavenly forces, next would consider the earthly forces, the physical considerations of wind direction and sun position would decide the height and orientation of buildings. The human factor would be considered lastly: the position of the site, the surroundings around the area, the main entrance and how air circulation would be, the gathering and flowing forces… etc. As all the forces (Heavenly, Earthly, physical, spiritual) in the universe are in harmony, no matter how big or small the garden is, the experience of being in it can’t be any better.

The success at this garden is the experience that intrigues our imaginations. Oriental gardens always create unlimited space in a limited area by not showing everything at once, this technique creates extension and contrast in a dramatic way. This technique combine with the art of borrowing, make the visitors become a subject of inter-borrowing, which can create the harmony between man and nature in just a small piece of land.

Figure 35. Curvy walkway flowing among the hills, bringing new views to visitors in every step (HK Govt, 2006).

Figure 36. One of the undulating stone paths through the woods.

Some might consider the essence of ancient oriental gardening as the journey “from physical to spiritual” experience. When one goes through different forms and spaces, one should not simply consider the physical appearance of a place, but its spiritual atmosphere that one experiences through rhythm and pace, and the journey of breathing. According to the garden’s web site, “Not only are the objects and arrangements within the garden important, so are the images and feelings they evoke. This kind of evocation works well in the aesthetic of poetry.”

Figure 37. Pamphlets maps handed out to visitors. The map shows all the attraction elements in the garden (HK Govt, 2006) .

Figure 38. An enlarged section of the map of Nan Lian Garden. “A”, “B”, “C” and “D” are positions from where the following photos were taken.

Figure 39. Photos taken at position “A” and “B”: The surrounding tall buildings do not bother the view as it is blocked by the trees nearby and blends into the backdrop with the mountains and sky.

Figure 40. Photos taken at position “C” and “D”: Examples demonstrating the art of borrowing. Borrowing mountains as a backdrop and the reflection of sky in the lake create unlimited imagination. The pavilion borrows the trees and the lake to combine as a mystical scenery.

Comparing Alnwick Garden & Nan Lian Garden

After experiencing the typical classical East and West gardens. There are a lot of differences in their design approach and ways of treating nature. Both gardens would have their supporters supporting their unique beauty.

For Alnwick garden, its beauty could only be appreciated in the summer when all the flowers bloom. The garden is closed in winter except the pavilion area for Christmas events. The photos seen above were taken in April 2011. It was spring but the flower booths were still empty. There are a number of open spaces in the park, which has its advantages and disadvantages. They would look good under the sun when the colour of nature were most vibrant, but once the weather turns chilly and people avoid the garden, the atmosphere would be eerie.

It is obvious that a good designed garden does not depend on its size or the environment it is situated at. Nan Lian Garden shows us that no matter how crowded or polluted its surroundings are, we can still enjoy the retreat in a small area as long as everything is in harmony. The advantage of being in the middle of the city gives the public opportunities to visit the garden whenever they like. Since the purpose of the garden is for meditation, the garden is planted full of evergreen trees. It is not common to plant wild flowers in an oriental garden. The twining paths are narrow and trees are close enough to let one feel accompanied. In that case, the less populated the better, so the visitor can fully absorb the trees’ presence.

If an urban dweller has to choose one of them to visit during winter, Nan Lian Garden would be the only option. There would not be empty flower booths or bare twigs around the garden but ever green pine trees. The beauty is in the spiritual form, line and pace. Such qualities makes Nan Lian garden a more successful tourist site than Alnwick Garden.

Conclusion

In the end, do we present the same meaning in different languages or are we interpreting the same words in different ways?

In the East, the importance of harmony lies on the spiritual and physical combination of all elements. It follows the rules of nature. In the West, the importance lies on form and space to create an ordered and picturesque effect. It is imposing man’s position over nature. The compromising mixture of the two might be a new trend for contemporary architectural design.

The universal beauty in art would be our true nature. As Christopher Alexander mentions in his work The Timeless Way of Building (1979), The elements that make us feel alive are the true beauty that can last forever.

As we are part of nature ourselves, we should always relate to nature, to go back to our true selves. The five natural elements (Metal, Wood, Water, Fire, Earth) can always be seen in our daily lives, as long as we can connect to some of these elements, be it artificial or natural, East or West, we could feel the presence of nature. The poet Tao had resolved this mystery in his poem centuries ago:

“In the remote heart, every place is a retreat.”

If we can sense nature’s existence with peace within our urban life, nature and man are in harmony, whether it is in the wild or in urban cities.

Figure 41. Water Lily in Nan Lian Garden.

References

Books:

• Alexander, C. (1979) The Timeless Way of Building. New York, USA: Oxford University Press

• Ji, C. (1988) The Craft of Gardens. New Haven and London, UK: Yale University Press

• Kassler, E. B. (1964) Modern Gardens and the Landscape. Revised edn. New York, USA: The Museum of Modern Art

• Richardson, T. (2008) Avant Gardeners. UK: Thames & Hudson Ltd

• Saunders, W. S. (Ed.) (2012) Designed Ecologies: The Landscape Architecture of Kongjian Yu. Switzerland: Birkhauser Basel

Electronic Journals:

• A. Y (2012) ‘Frank Lloyd Wright and Japanese art: Heaven, closer to Earth’. The Economist. Available at: http://www.economist.com/blogs/prospero/2012/10/frank-lloyd-wright-and-japanese-art (Accessed: 10th Nov, 2012)

• Huang, Y. (2005) ‘China’s First Participation to the World Expo’, World Expo Magazine, issue 5, 2005 [Online] Available at: http://www.expo2010.cn/expo/expoenglish/wem/0505/userobject1ai36183.html (Accessed: 10th Nov, 2012)

• ‘Garden design: Power plants’ The Economist (2001) [Online] Available at: http://www.economist.com/node/561682 (Accessed: 24th Dec,2012)

Online Blogs:

• Larson, T. (2012) ‘An imperial imprint’ ArchiTalk. 15 May. Available at: http://architalk-tlarson.blogspot.co.uk/2012/05/imperial-imprint.html (Accessed: 10th Nov,2012)

Department Publications:

• China. The Bureau of Shanghai World Expo Coordination (2010), When did China join BIE? [Online]. Available at: http://www.expo2010.cn/expo/english/ac/faq/userobject1ai9325.html (Accessed: 10th Nov,2012)

Television Interviews:

• Saunders, W. S. (2012) CCTV-13 News, 3 Oct [Online]. Available at: http://www.turenscape.com/online/showvideo.php?id=38 (Accessed: 24th Dec,2012)

Seminars:

• Yu, K. J. (2011) Big Foot Revolution. [Lecture to IFLA World Congress]. 28 June [Online]. Available at: http://www.landscape.cn/News/info/2011/250721399.html (Accessed: 24th Dec,2012)

Figures:

• Fallingwater org (2013) FW Fall 04 [Online] Available at: http://www.fallingwater.org/(Accessed: 6th Jan,2013)

• Farooqi, S. (2012) Alnwick Garden Map.[pen and watercolour] Alnwick Garden [Online]. Available at: http://www.nationalartandcraft.com/art.php?ArtID=1777 (Accessed: 24th Dec,2012)

• Galland, E. (2005) Lipstick Forest 14. [Online]. Available at: http://www.claudecormier.com/project/lipstick-forest/(Accessed: 24th Dec,2012)

• GoogleMaps (2013) ‘White House, Washington, DC, United States’ Google[Online] Available at: https://maps.google.com/(Accessed: 6th Jan,2013)

• GoogleMaps (2013) ‘Alnwick Garden Enterprises, United Kingdom’ Google[Online] Available at: https://maps.google.com/(Accessed: 6th Jan,2013)

• HK Govt (2006) Overview 3. [Online] Available at: http://www.nanliangarden.org/contentpages/90/20070326_20061123_Overview_3.jpg (Accessed: 24th Dec,2012)

• HK Govt (2001) The Garden Site: 2001[Online] Available at: http://www.nanliangarden.org/concept.php?ss=29(Accessed: 24th Dec,2012)

• HK Govt (2006) The Aesthetics of Resonance. [Online] Available at: http://www.nanliangarden.org/art.php(Accessed: 24th Dec,2012)

• http://www.iching.com.my/loupan-en.htm (2012) (Accessed: 24th Dec,2012)

• Kassler, E. B. (1964) Modern Gardens and the Landscape. USA: The Museum of Modern Art, pp.4,illus.

• Larson, T (2012) Imperial Hotel Wright House Cropped [Online] Available at: http://architalk-tlarson.blogspot.co.uk/2012/05/imperial-imprint.html (Accessed: 24th Dec,2012)

• Petro Photo (no date), 35/43 Pictures, Vaux le Vicomte Garden, France, Local Name: Jardin de Vaux le Vicomte, Petro Photo [Online]. Available at: http://en.petrophoto.net/wallpaper-vaux-le-vicomte-garden-43-1485.htm(Accessed: 6th Jan,2013)

• Scazenave (no date), Vaux le Vicomte. Flickr [Online]. Available at: http://pinterest.com/pin/172051648235426820/(Accessed: 6th Jan,2013)

• Turenscape (2008) Qinhuangdao Red Ribbon Park. [Online] Available at: http://www.turenscape.com/English/projects/project.php?id=336(Accessed: 24th Dec,2012)

• Vézina, J. F. (2003) Lipstick Forest 4. [Online]. Available at: http://www.claudecormier.com/project/lipstick-forest/(Accessed: 24th Dec,2012)

• Vézina, J. F. et al. (2003) Lipstick Forest 12. [Online]. Available at: http://www.claudecormier.com/project/lipstick-forest/(Accessed: 24th Dec,2012)

• Vézina, J. F. (2003) Lipstick Forest 13. [Online]. Available at: http://www.claudecormier.com/project/lipstick-forest/(Accessed: 24th Dec,2012)

• Wirtz NV (1999) Alnwick 1. [Online] Available at: http://www.wirtznv.be/en/projecten/openbaar/alnwick/1/(Accessed: 24th Dec,2012)

Web sites:

• Alnwick Garden official web site:

http://www.alnwickgarden.com

• Claude Cormier’s Architectural Company web site:

www.claudecormier.com

• Fallingwater official web site:

http://www.fallingwater.org/

• Nan Lian Garden official web site:

http://www.nanliangarden.org

• The 48th IFLA World Congress official web site: http://landscape.cn/Special/ifla2011/

• Wirtz International Landscape Architects:

http://www.wirtznv.be/en/intro/

• Yu K. J.’s Turenscape web site:

http://www.turenscape.com

Results

This essay received a grade of B-.